Tiny, inked clusters of needles jut out of a miniature cactus on Bianca Martinez’s ankle. Her first tattoo, she got it to remind herself where she came from.

“Reynosa in Tamaulipas, Mexico,” she said, trilling her “r”s and rolling her “l”s in all the right places.

However, she identifies just as much as American as she does Mexican, though that doesn’t mean that she is allowed the same rights as her peers.

Enacted under former President Barack Obama’s administration, the DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) administrative program protects qualified “Dreamers” from deportation and prosecution. The program, which has been in effect since 2012, does not grant citizenship. It does not convey legal status but allows undocumented immigrants who were not older than 30 years old when DACA was enacted and younger than 16 when they entered the country to work without fear of deportation. The act is not a law, and those it protects face uncertain futures.

As an Ole Miss student living under DACA protections, Martinez is relegated to being stuck in limbo — somewhere between being a citizen and not.

Bianca Martinez is an Ole Miss students, living in the United States DACA protection. Photo by Devna Bose

HER PAST

Martinez and her family moved to Texas before settling when she was 5 in Itta Bena, Mississippi — one of the poorest towns in the poorest state in America. Her parents are undocumented, her two siblings who were born in the U.S. are citizens and Martinez received DACA status a week before she turned 15.

She doesn’t remember many complications resulting from her status or her parents’ illegal immigration as a child, though there were a few notable issues.

“We are a low-income family, so we couldn’t afford a lot of things, but we couldn’t get food stamps or anything like that,” she said. “A lot of my time was spent with my parents helping them do things that 11-year-olds aren’t normally doing, like helping them get insurance.”

However, as an adult, Martinez has had to overcome many hurdles to get to where she is today.

“As I grew up, I think it affected me more because I was so hopeful about going to school and getting a career,” she said. “But I realized if I didn’t have a Social Security card, I wouldn’t be able to go.”

Those without a Social Security number can still apply to college but are unable to receive state and federal financial aid, making the process of attending higher education more difficult.

Compared to Martinez, her siblings will be able to attend a university more easily, which is something she used to be jealous about.

“I was so jealous, and I used to blame my parents for that. I thought that my parents should have come here earlier or stayed in Mexico,” she said. “But now, I’m happy for my siblings. I’m happy the path for them will be so much easier.”

A graduate of the Mississippi School for Math and Science and a current senior biology major, Martinez takes classes at Ole Miss and works 25-hour weeks to pay for them.

“I don’t get the point of having to prove myself, even though I feel like I’ve done that pretty well. I’ve worked really hard in school, and I used to work 60 hours a week just to make money to go to school,” she said. “Not that citizens don’t do that, but if you’re low-income, you can get money from the government — I can’t even do that with all these credentials, and that’s not fair.”

Local immigration lawyer Tommy Rosser said that he deals with a number of “Dreamers” in Oxford, and most of them have not gone on to pursue educational opportunities past high school.

“There has been a problem with certain community colleges and institutions resisting allowing DACA kids to move forward to (the) college level,” Rosser said. “Particularly in Mississippi, there has been resistance to accepting them.”

In Mississippi, to be able to attend an institution of higher education as a “Dreamer,” college administrations have to accept documentation, which is usually an employment authorization form.

“On that basis, they then go and get a Social Security card that allows them to get a driver’s license and temporarily have identification,” he said. “Some schools have resisted to that sensibility.”

Martinez described having constant anxiety about her future as a result of her DACA status.

“There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t think about it. My grades suffer because I’m constantly thinking about making money for school,” she said, her voice cracking. “I’m poor. I’m brown. I’m a woman. I can’t be uneducated, too.”

HER PRESENT

Martinez remembers the night of the 2016 presidential election, watching the states on television stain red slowly but surely across the country.

“I remember a girl coming in the dorm lobby where I was watching the election, and she walking in and said, ‘Donald Trump is for God. There will be no more immigrants, no more (this and that).’ I just got up and went for a walk,” she recalled. “Then, the next morning, I had a panic attack in the shower.”

While living in Oxford, she’s encountered various forms of hatred to her face.

“It’s so easy for people to point out what’s wrong with immigrants. People don’t realize they’re being ignorant and hateful at the same time. Like, that stuff hurts because I’m an immigrant, and I am none of those things that Trump says,” she said. “(Trump) gives them the green light to say these things.”

Bianca Martinez is an Ole Miss student, living in the United States DACA protection. Photo by Devna Bose

The current election cycle has been hard on Martinez — people protected under DACA don’t have the right to vote.

“It sucks. I want to be able to share my voice,” she said. “I feel like I’m the best person to represent me, but I can’t do that. Decisions about DACA kids are being made by white men, not DACA kids or even people who live with kids protected under DACA. I’m the conversation, but I’m not allowed to be a part of the conversation.”

However, she stays involved to make sure others have a voice, even when she doesn’t. All while working and taking classes, Martinez is a member of College Democrats, vice president of Students Against Social Injustice (SASI) and actively participates in a number of protests on campus.

“I want us to work together to work on each other’s struggles,” she said. “One voice isn’t enough, and everyone’s voice is valid.”

And Martinez makes sure she’s heard.

“I give myself a voice,” she said, through being outspoken in protests and on social media.

Former president of SASI Taia McAfee described Martinez as a “great help to the movement,” attributing her impact to Martinez’s strong presence.

“When she joined SASI at the beginning of this year, it’s like the organizer in her had been bottled up so long, and it got let out,” she said. “She’s able to move folks to actually do something, and it’s a skill not many have. I’m so grateful she’s a core member of SASI because our work wouldn’t be the same without her.”

Martinez’s roommate and SASI secretary Em Gill said Martinez is an invaluable asset to the SASI organization because of her passion.

“It’s so amazing to feed off her passion,” they said. “She’s really empathetic and genuinely cares about people, cares actively.”

Gill, who identifies as non-binary and transgender, said they relate to Martinez because of their shared experiences of oppression.

“We talk a lot about our experiences, just as friends and as marginalized people,” they said. “We complain to each other about how we’re treated in class, and I know she’s had issues with coworkers and professors, too. We discuss how it’s not a personal thing. It’s a larger problem and not our fault. It’s healthy to have those types of discussions about how we fit into a bigger picture.”

Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs Brandi Hephner LaBanc, who could not be reached for comment at the time of publication, released a statement last September in response to Trump’s attempt to rescind the DACA Act in which she cited the University Counseling Center, Office of Global Engagement, Office of the Vice Chancellor for Diversity & Community Engagement and Office of the Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs as places where students can seek direction or advice. Two years ago, the Associated Student Body discussed options for protecting “Dreamers” on campus, though discussions were tabled. Gill believes the university should do more.

“I wish that, institutionally, the school would acknowledge and recognize that there are students like Bianca who are DACA recipients. She’s not the only one, and I know especially during this politically tense time, she and all of them have to feel so isolated and cut off,” they said. “If our university does care about our students, which it should, then it should definitely have some sort of support system, somewhere they can go to specifically for help.”

Martinez’s close friends like Gill and McAfee know that she is a “Dreamer,” but it’s not something she openly shares. Sometimes, she mentions it in passing, and though she appreciates the sympathy that people often give, it’s not what she wants. Instead, Martinez wants action.

“I recently met this man who was saying things like, ‘I don’t care if Mexicans come into the country; I don’t believe what (Trump) says,’” she said. “That’s cool and all, but I’m not the one you’re supposed to be convincing. I know we’re not bad people. Go tell your white friends that.”

HER FUTURE

President Donald Trump attempted to the rescind the act last year, but federal courts have since ruled DACA constitutional through a temporary injunction that allows it to continue to protect those who were previously covered. However, there is no clear pathway for “Dreamers” to obtain citizenship. They don’t have the same rights as American citizens, but they can’t leave the country, either.

According to Rosser, “All they can hope for is that some sort of determination will be made by Congress in terms of passing the proposed DREAM Act or (a) similar remedy that will allow them to move forward to a resident status.”

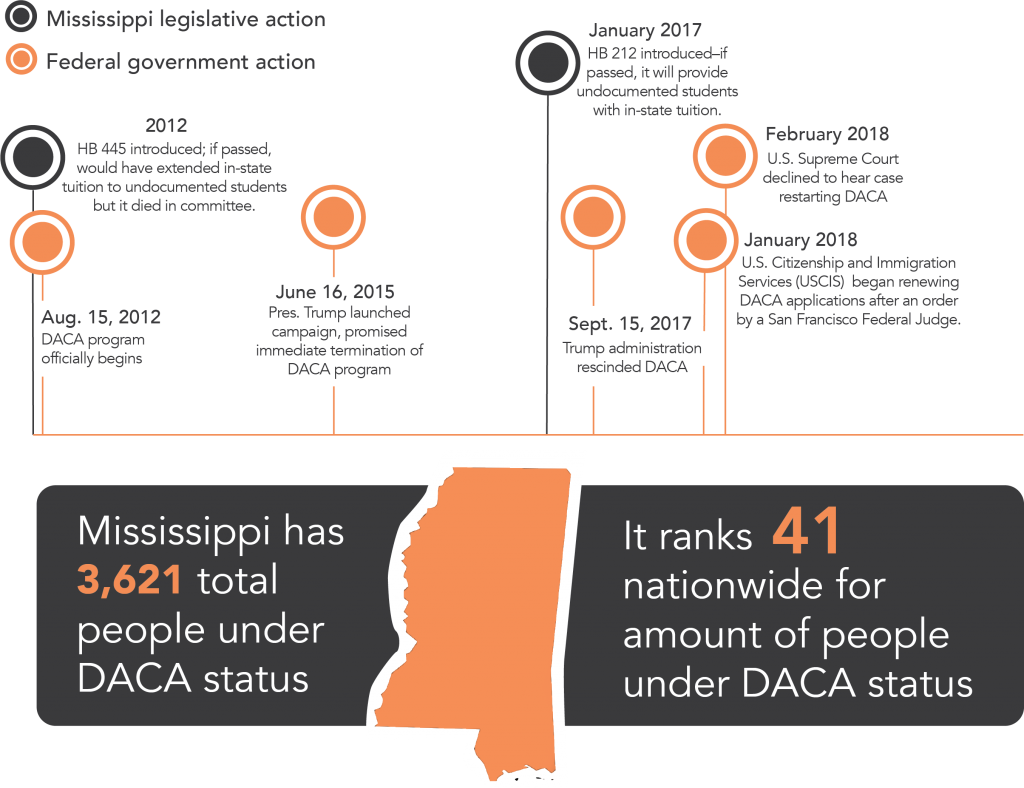

Graphic illustration: Hayden Benge

Ole Miss political science professor Gregory Love describes the future of these people as “uncertain.”

“It’s very unclear what’s going to happen, and that’s because, of course, DACA was not a law,” he said. “DACA is basically the executive branch saying, ‘We’re not going to prosecute you,’ but it doesn’t give you a pass into the system.”

Though the popularity of the “program” is relatively high, under the current political climate, Love doesn’t foresee a definitive decision in the imminent future for “Dreamers.”

“Getting a change to the immigration policy seems highly unlikely,” Love said.

Martinez is split on her opinion of DACA and just wants some sort of decision to be made.

“I am grateful for Obama and what his administration did, but it also just feels really half-assed because I have half-rights basically,” she said. “I don’t want DACA to end because it is a gateway for a lot of people, but I do want DACA to move forward into trying to get people citizenship and give people more rights.”

She is hoping, after graduation, to be a teacher and lead young minds, but for now, “bitter” is the word that comes to Martinez’s mind, the word she repeats, over and over.

“It’s not like I had a choice — I shouldn’t be punished for coming here. I’m human, and I don’t know why people can’t see that. All humans have the right to live where they feel safe,” she said, eyes flooding over. “People are out here just trying to live, you know?”