Filling the wooden pews that line the sanctuary of Second Baptist Church on Jackson Ave., a sea of black and white faces sat as one, bound together in remembrance of Elwood Higginbottom.

Efforts to memorialize the 1935 lynching of Higginbottom were cemented during a ceremony at the church on Saturday afternoon.

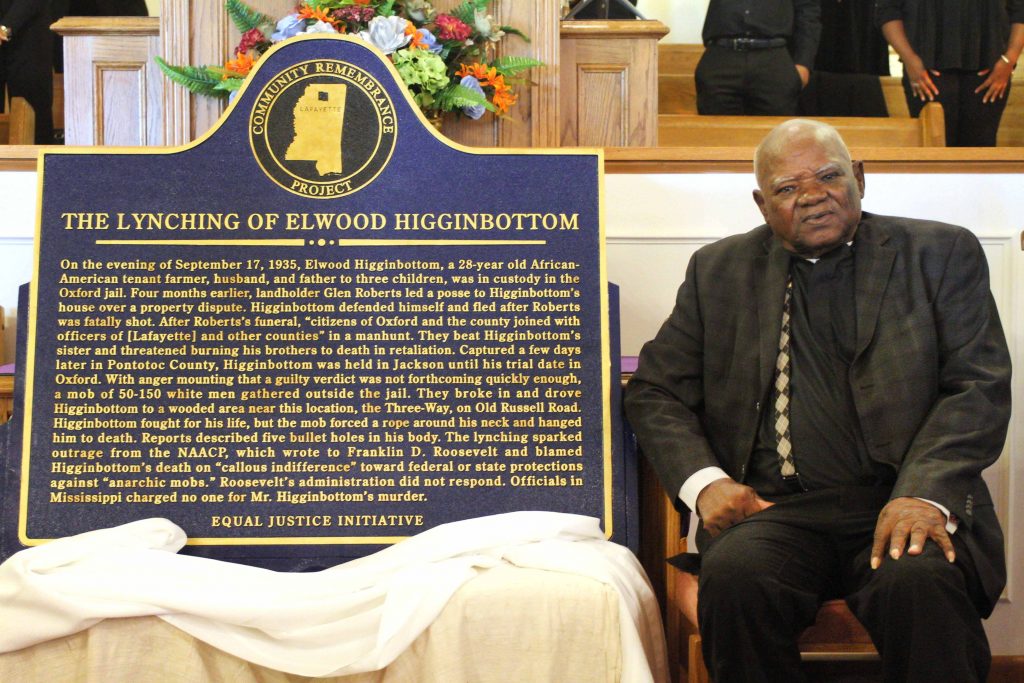

E.W. Higginbottom, the son of Elwood Higginbottom who was the seventh and last recorded person to be lynched in Lafayette County, sits in Second Baptist Church during the dedication of a new plaque to memorialize his father. Photo by Reed Jones

A large marker details the events leading to Higginbottom’s murder and the fact that the perpetrators went unpunished. The plaque will sit at the “Three Way” intersection of Molly Barr Road and North Lamar Boulevard — the location where Higginbottom was killed.

The ceremony lasted more than two hours and included performances from the UM Gospel Choir, a rendition of Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” by Oxford singer Effie Burt and a song performed by Higginbottom’s descendants and relatives.

Between performances, April Grayson, director of community building with the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation, introduced the descendants of Higginbottom who were in attendance. His oldest son, E.W. Higginbottom, the only living direct descendant, sat on the front row with his six children and grandchildren. Members of the Higginbottom family traveled from Memphis, and as far away as Ohio and Texas, for the event.

Evan Milligan of the Equal Justice Initiative joined other EJI representatives at Sunday’s event. The EJI is a non-profit organization based in Montgomery, Alabama, that delivers legal representation and social services to those treated unjustly in the judicial and penal system.

“Why are we so comfortable having a system where so many people are thrown away? Why are we so comfortable with a system with young people born into conditions of homelessness? We have a problem with that,” Milligan said. “In order to address that problem, we can’t only talk about laws and policies. We have to talk about our hearts and cultures and stories that we tell each other. The desire to have that conversation is why we began to work with this (Higginbottom) case.”

In conjunction with the Winter Institute, the Higginbottom family and the Lafayette County community, the EJI worked to develop a plan for the plaque and donated the funds to assure its completion.

A new plaque was dedicated on Saturday to memorialize Elwood Higginbottom, the last man to be lynched in Lafayette County in 1935. Photo by Reed Jones

Louis Burroughs from Cleveland, Ohio, grandnephew of Elwood Higginbottom, delivered the day’s closing remarks.

“My mother and grandmother spoke of lynching as though they had been here, although they migrated from Oxford,” Burroughs said.

After Elwood Higginbottom’s lynching, Burroughs’ grandmother loaded the family into a school bus and fled Oxford under the cover of night.

Burroughs said he wasn’t aware he was related to Elwood Higginbottom until reading the New York Times Magazine piece written by UM journalism professor Vanessa Gregory.

Burroughs has refused to accept the way his grand uncle’s story and death were portrayed by newspapers at the time.

“They wrote that Elwood was an unlettered man, a man holding a grudge,” Burroughs said. “They attempted to reduce him to a cowardly, illiterate sharecropper deserving of being demonized.”

Instead, Burroughs prefers his family’s account of events.

“Elwood was killed in cold blood for no other reason than being a man,” he said. “He was defending his children, his wife and his home. Had the jury been allowed to reach a verdict, he would have been undoubtedly found innocent, for reasons of self defense — a basic human right.”

Burroughs concluded by asking the audience a question about the power of visual symbols — the very reason for Saturday’s gathering.

“What would the city of Oxford and the town square look like if the monument to the Confederate soldier was replaced by a monument to the brave black men of Mississippi?”

Descendants and relatives of Elwood Higginbottom sing for the audience of Second Baptist Church during the dedication of a plaque to memorialize Higginbottom, a man who was lynched in 1935. Photo by Reed Jones

The EJI held an essay contest for local high school students that asked participants to compare a historical injustice to contemporary issues.

The top four winners were recognized at the ceremony, and Jupiter O’Donnell—a junior from Oxford High School— read his aloud to the crowd. His four minute essay about police brutality garnered a unanimous roar of approval and a standing ovation.

“It’s so important for us to be able to understand our contemporary challenges through the lens of our history. If we want to know how we move forward and heal, then we have to commit ourselves to truth telling,” said Kiara Boone, the EJI’s deputy director of community education. “Sometimes the truth is difficult, sometimes the truth painful and hurtful, but what it is always is the truth.”