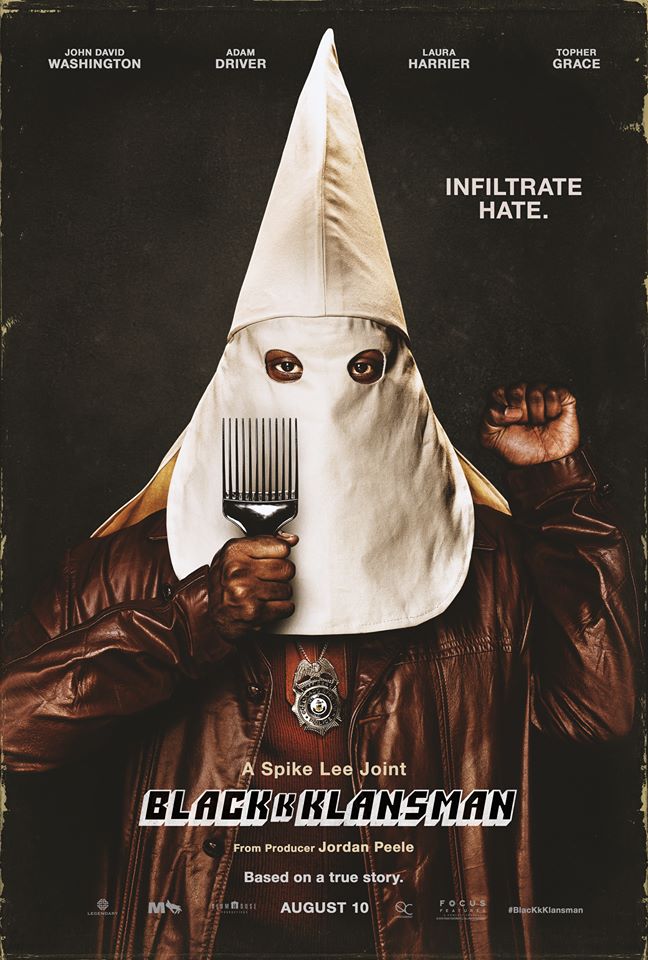

Photo Courtesy: “BlacKkKlansman” Facebook page

The latest Spike Lee joint, “BlacKkKlansman,” tells the “crazy, outrageous, incredible” story of a black man who infiltrated the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1970s. Although the film is set nearly 30 years in the past, its narrative and themes resound in today’s political climate, and the kicker is that it’s based on a true story.

“BlacKkKlansman” depicts the life of Ron Stallworth (John David Washington), the first black police officer in Colorado Springs, Colorado. After Stallworth is transferred to the intelligence department, he finds an ad in the paper for the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan and makes a call in which he pretends to have interest in joining the organization.

Stallworth’s partner Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver) goes undercover as “Ron Stallworth” while the real Stallworth keeps up the identity over the phone. The investigation leads them to the center of Colorado Springs’ network of white nationalists, a meeting with Grand Wizard David Duke (Topher Grace) and a rush to thwart a plan by the Klan.

Despite the intelligence Stallworth gathers, his investigation brings pressure from the police chief and a confusing romantic relationship with Patrice Dumas (Laura Harrier), the president of the Colorado College Black Student Union and a locally known activist.

Like the officers whose story it tells, the film investigates and interrogates a wide range of topics including police brutality, white nationalism, racism and the resistance of the black community to all these facets of white supremacy.

Recently, left-wing activists have accused the media of normalizing the radical viewpoints of white supremacists by publishing profiles of white nationalists, including one published in The New York Times in November 2017. Lee seems to ignore this criticism and deeply explores the everyday lives of white nationalists.

The film also has an element of black power organizing, but scenes of the Klan dominate screen time. This intense focus on the Klan’s activities — which include cross burnings, discussion of plans to kill black people and countless racial slurs — does make the film hard to watch at times.

But Lee’s retelling of Stallworth’s story is also about resistance from the inside. An outsider to both the obviously racist Klan and the Colorado Springs Police Department, which has a history of brutality against the city’s black residents, Stallworth is able to infiltrate both organizations.

Lee’s film could be viewed as a crime drama, because the film continually shifts between the detectives’ and the Klan members’ perspectives, creating tension and suspense as both groups try to uncover each other’s secrets and plans. Like other Lee movies, however, the primary intent of “BlacKkKlansman” is to send a powerful message its viewers.

The movie seemed to drag on until its final minutes, during which the pace picked up with startling intensity. I was speechless, breathing heavy and on the verge of tears. In near silence, I could hear similar reactions from the crowd, even though there weren’t more than 10 people in the theatre.

Though the story “BlacKkKlansman” tells happened decades ago, Lee’s presentation of the narrative feels closely connected to current events, especially when one considers its release date, which was right around the one-year anniversary of the white nationalist march and ensuing riots in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017.

The film’s script, written by Charlie Wachtel, David Rabinowitz, Kevin Willmot and Lee, includes several direct allusions to politics in the era of Donald Trump.

For example, in the film’s opening scene, a talking-head Southerner named Dr. Kennebrew Beauregard (Alec Baldwin) refers to black people as “murderers and rapists” in the way that Trump referred to Mexican immigrants when he said, “They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.”

Beauregard makes a reference to “superpredators,” a word lifted directly from a 1996 speech given by Hillary Clinton in support of increased policing.

As these references came up, they seemed a bit forced. But, when considering the film as a whole, they were small, necessary links to connect Stallworth’s story to the present day.

“BlacKkKlansman” features plenty of ‘70s black culture, such as funk and soul music, as well as casual references to Blaxploitation films such as “Shaft” and “Coffy.” Visually, Lee uses split screens and fonts that allude to ‘70s style, and the film has a color palette full of wood paneling and dark leather.

With details like this, “BlacKkKlansman” is somehow as specific to the ‘70s as it is to the present day. It is as thrilling and important a story now as it was then.