From 2005 through 2009, the women of the Manitoba Mennonite colony in Bolivia woke up with strange aches and pains. When they asked the community’s male authorities what was happening to them, the men told them that nocturnal demons were attacking them for their sins.

In reality, a small group of the community’s men had been repeatedly drugging the women with animal tranquilizers and raping them in their sleep. Some of the rapists were punished, but the situation still posed grisly theological, physical and emotional questions for the victims.

How could they live as Mennonites, forgive like Jesus or even believe in God following this brutality?

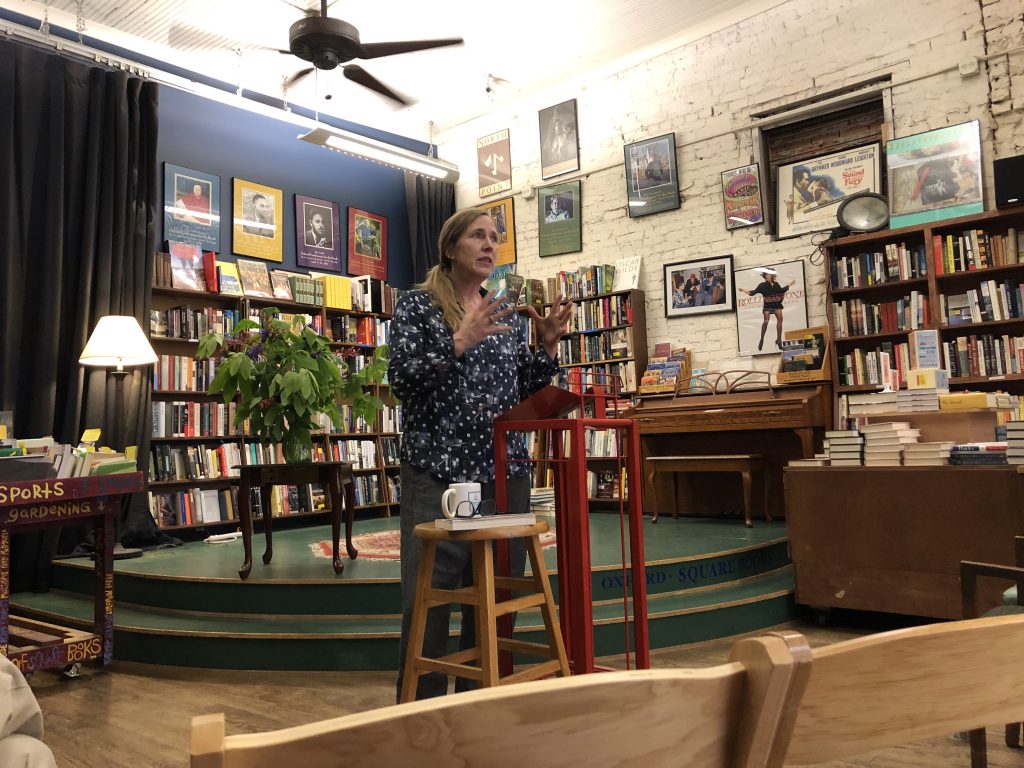

Miriam Toews, a Canadian author of seven previous books, reckons with the aftermath of these horrific attacks in her latest book, “Women Talking.” She read from the novel and discussed it with audience members at Off Square Books last night.

“Women Talking” presents the fictional discussions these Mennonite women may have had after the attacks. In the novel, most of community’s men have gone to town to post bail for the rapists, leaving the women and August Epp, an ostracized male teacher, alone in a barn for 48 hours to sort through the tragedy.

Since all of the women are illiterate, the book is presented as the minutes of their meetings, written down by August. He is given this task by Ona Friesen, the woman he loves.

“(Ona and I) had this conversation last evening, standing on the dirt path between her house and the shed where I’ve been lodged since returning to the colony seven months ago,” August writes in some of the novel’s opening lines. “A temporary arrangement according to Peters, the Bishop of Molotschna. Temporary could mean any length of time because Peters isn’t committed to a conventional understanding of hours or days.”

This short passage hits on the “culture of control,” centered on an authority topped by clergymen, which Toews said she aims to critique with the book.

“I’m not being critical of the Mennonite faith or the people themselves but of that culture of control,” Toews said. “I think it’s something I … can’t let go.”

When asked why she chose to write the book as the minutes rather than from one of the women’s perspective, Toews said she feels the need to give her characters “assignments.” For instance, her 2004 novel “A Complicated Kindness,” is literally a school assignment given to its sixteen-year-old main character, Nomi Nickel.

“I’ve always been sort of afflicted with the futility of what it is I’m doing … in order for it to seem like a useful thing, I have to give myself an assignment,” Toews said. “Maybe it’s because my father was a schoolteacher. He gave me little assignments. Who knows?”

Toward the end of the question-and-answer session, Toews admitted that although she doesn’t believe in God, she often finds herself practicing a form of prayer.

“I pray for my family and for my, you know, my children, for my grandchildren, for my friends, and my mother, and I pray for their safety and happiness,” she said. “But I also pray for these women in the Manitoba colony and I think of the book sometimes … as a kind of a prayer.”