“How many in here are wrestling fans?” Christopher Stacey asked as he stepped out into the corridor created by rows of tables in the Tupelo Room of Barnard Observatory. Roughly half of the two dozen people in the room raised their hands.

“How many in here are sports entertainment fans?” he asked, raising his voice before coming to his ultimate question: “Is there a difference?”

This is how Stacey opened “Three Histories of Pro Wrestling in the South,” a series of talks by Stacey and two other scholars of the South, Chuck Westmoreland and Charles Hughes. Students, faculty and Oxonians alike showed out for the lunchtime lectures on Wednesday — some coming with sandwiches and several coming with questions.

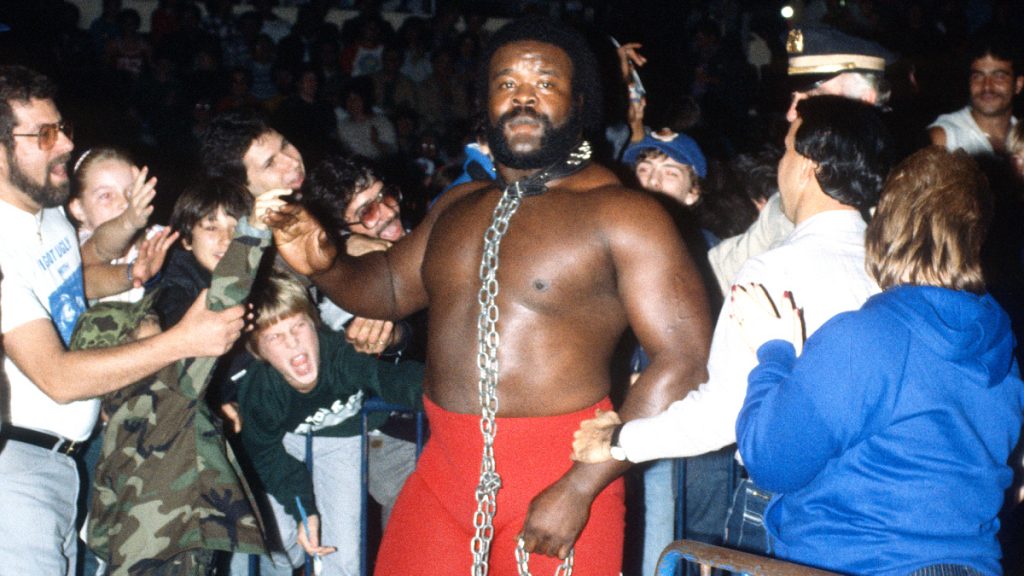

Photo Courtesy: WWE

Stacey, an associate professor of history at Louisiana State University of Alexandria, was on campus to argue the point of his final question — that there was little or no difference between pro wrestling and sports entertainment.

To underscore his point, Stacey showed a viral video of a man tearfully thanking a panel of pro wrestlers.

“I just want to thank each and everyone one of y’all for all you’ve done to your bodies,” the man says in the video. “It’s still real to me, dammit!”

Though fans bemoaned the exposure of pro wrestling fakery, also known as “kayfabe,” Stacey said that this change in marketing benefited scholars because it “opened Pandora’s box” of data for wrestling historians to explore. Before that, the behind-the-scenes shows, podcasts and books that inform their work didn’t exist.

Throughout the hour, the scholars talked with and about each other, referencing one another’s works and proving that they were familiar with them. These scholars didn’t see their ideas in isolation but as parts of a broader conversations about history, sports and the South.

The talks were short, with none clocking in at more than 15 minutes. The scholars buzzed from talk to talk, playing off each other’s energy like professional wrestlers in the ring.

Westmoreland, an associate professor of history at Delta State University, posited that scholars should view and think about pro wrestling as a sport, which in turns opens many avenues for academic inquiry.

“Through sport we can get a window into issues of race, gender, regionalism, politics, class, labor and many other aspects in a scholarly setting,” Westmoreland said.

For Westmoreland, pro wrestling is not only a scholarly interest — it’s personal.

“Growing up as a kid in southern Virginia, Saturday morning in the 1980s meant one thing: wrestling at noon on WTVR,” Westmoreland said. “And then, if my parents would let me stay up late, after the 11 o’clock news, another wrestling show would come on.”

Hughes, who teaches and directs the Lynne and Henry Turley Memphis Center at Rhodes College, said his work focuses on “the intersection of popular culture and American racial politics.” He used his time on Wednesday to directly address the connections between pro wrestling and race that Westmoreland hinted at.

“Building off some of the lenses that my colleagues are talking about, I found that, actually, there is a rich story — and an interesting one — about how African Americans have engaged with pro wrestling as performers and audience members,” Hughes said.

Hughes argued that pro wrestling played into stereotypes of black people but also served as a space for resistance. Even among racist storylines, one wrestler, the Junkyard Dog, emerged as a hero of black resistance in his fights against an explicitly neo-Confederate character throughout the South.

Pro wrestling, Hughes said, had more practical implications in the South, such as the desegregation of arenas at the behest of black performers and the hiring of black workers behind the scenes. In the 1990s, pro wrestling storylines even featured storylines that aligned with the “hip-hop wars,” which were stoking white fears throughout the U.S.

After the lecture, people in the crowd asked the scholars questions about about how pro wrestling intersected with reality television and the Trump presidency.

These lectures were the third event in a four-part series of brown bag talks about sports in the South hosted by the Center for the Study of Southern Culture. For the next event, Amira Rose Davis will discuss on Oct. 24 how “black women athletes have been hypervisible yet oft-ignored symbols of various political struggles.”