Whether the images are ones that people recall with nostalgia – pageant queens, all-American football stars and Greek Revival buildings – or those that people try to hide from – young men rioting at James Meredith’s admittance and bullet holes in the Lyceum’s columns – depictions of the University of Mississippi and Oxford during the civil rights era often show a place entirely defined by its oppressive white supremacy.

In many ways, these depictions are accurate. For a long time, Ole Miss, with its nickname deriving from plantation vernacular, existed as a place for the children of Mississippi’s aristocracy to receive their education. As R.L. Nave puts it in a Jackson Free Press article, Ole Miss was “a breeding ground for the South’s moneyed elite.”

The university’s country-club campus, which American Public Media describes as “perhaps the most hallowed symbol of white prestige in Mississippi,” seemed to exist only to build the status of the cheerleaders and student body presidents who would hold positions of power in the state.

But beneath Oxford’s veneer of marble and magnolia, there existed an oft-forgotten resistance.

Meredith’s 1962 integration may have most notably focused the public eye on Oxford, but events following the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. – which took place 50 years ago this week on April 4, 1968 – juxtapose an oppressive campus culture with a subtle resistance.

Meredith’s 1962 integration may have most notably focused the public eye on Oxford, but events following the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. – which took place 50 years ago this week on April 4, 1968 – juxtapose an oppressive campus culture with a subtle resistance.

UM alumnus Michael McMurray participated in a march from campus to the Burns Methodist Episcopal Church following King’s assassination. According to McMurray, many black students and Oxford residents joined in singing “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around” to honor King’s life.

According to the April 8, 1968, edition of The Daily Mississippian, this march ended with a small service on the Square. The Daily Mississippian also reported on a small gathering around the flagpole in the Circle “to protest the fact that the American flag was not being flown,” which resulted in the administration flying the flag at half-staff.

Letters to The DM and editor Jerry Doolittle’s strange decision to publish an editorial written by Pastor Jim Bain of North Oxford Baptist Church that focused on nationwide riots while ignoring the racism that caused King’s assassination show that many white students were far from agreeing with those who marched, but that doesn’t negate that they did.

The events in Oxford that week remarkably found their way into a 1969 Sports Illustrated article by Pat Ryan titled “Once It Was Only Sis-Boom-Bah!” about cheerleading traditions at colleges across the country.

About the march, Ryan writes that “black Ole Miss students … marched in a solemn procession up a street where campaigning cheerleaders were promising voters such things as a free supply of Rebel flags,” exposing the poetic dissonance of the campus in the late 1960s.

By the time of the 1968 march, most overt signs of segregation had disappeared from Oxford, but some of its vestiges remained. According to McMurray, in the week after King’s death, Jim Crow finally left, which McMurray believes was sparked by the response to King’s assassination.

At the time, the Wesley Foundation operated a coffeehouse near campus. This was the first voluntarily integrated structure in Oxford and became a space for black and white students to meet in a community that otherwise prevented this from happening.

While the Wesley House was a space for meeting between races, churches such as Burns became sanctuaries and meeting places for Oxford’s black community. Burns, which is now a museum and multicultural center, hosted NAACP meetings and helped organize the march following King’s assassination.

After the parish moved to a new church on Molly Barr Road, Burns-Belfry became a meeting space for the Oxford Development Association and home of its archives.

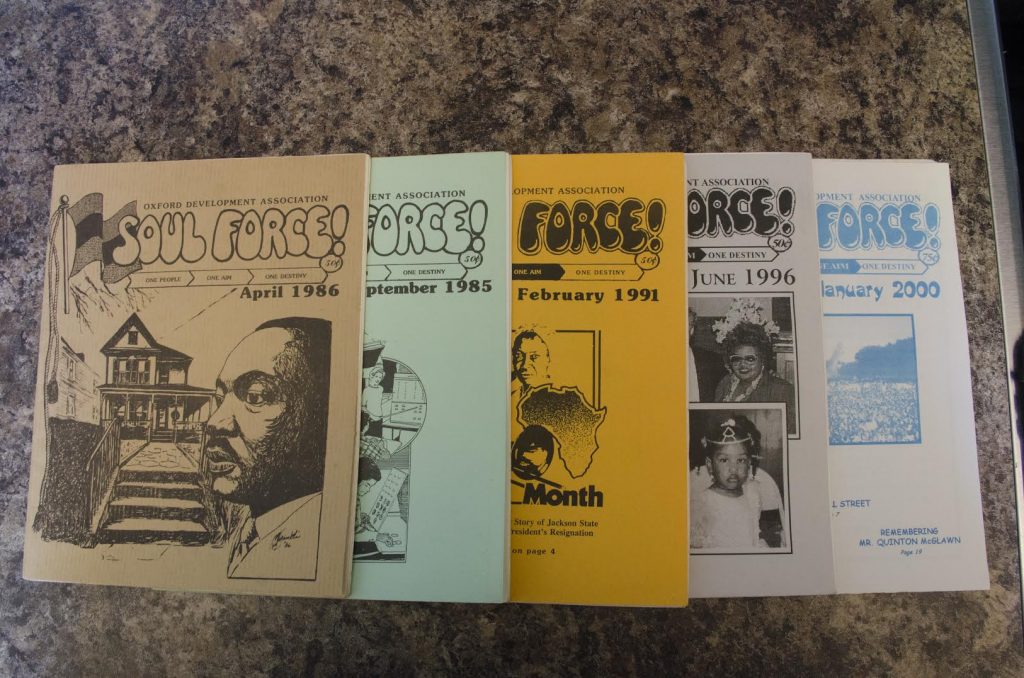

The ODA, an organization with the goals of promoting education and making general improvements within Oxford’s black community, was formed in 1970. It hosted yearly events, sponsored scholarships for medical school and published a newsletter called Soul Force.

The issues of Soul Force, many of which are housed at Burns-Belfry, tell a story of Oxford’s black community’s commitment to local issues and of awareness of the historical and geographical scope of the civil rights movement.

Articles detail the lives of figures such as Wayne Johnson, an Oxford-born, Atlanta-trained minister who returned to Oxford in 1969 to help the community that raised him by founding the ODA.

As the June 1996 article explains, Johnson mentored black students in the late 1960s and early 1970s as they navigated the newly integrated campus and organized a carpool “for African-Americans to become part of the political process and use their vote.”

In another piece, published posthumously, ODA president, longtime educator and namesake of an Oxford elementary school Della Davidson tells her “Own True Story.”

Davidson writes of how she found her passion for teaching and received her education at Rust College, Fisk University and Atlanta University. She taught in Oxford and Taylor for 33 years before becoming principal at Bramlett Elementary a mere 11 years after Oxford’s schools integrated.

“Davidson’s life touched so many people it would be impossible to overestimate her influence. Through her commitment to education, she helped mold the characters of generation after generation,” writes an unnamed contributor in a memorial to her life.

A recurring “Tidbits from the Countryside” section and a calendar of local birthdays speak to how involved the ODA was in Oxford’s tight-knit black community, while a cover urging readers to “Divest Now!” from businesses that support South African apartheid suggests a global scope to the work of this small-town organization.

And today, the work of campus activists is rooted in important local issues, though it resounds across the country.

For example, the work of Tysianna Marino and Dominique Scott, profiled by professor Brian Foster in an article for Parts Unknown, centered on campaigning for the administration to take down the Mississippi state flag on campus. However, this local effort can serve as an example for activists grappling with symbols of the Old South in their own towns.

We should remember what Ole Miss was – a stronghold of white supremacy and the Old South – but recognize and be inspired by what existed underneath that – the hard work of townspeople and students for civil rights in Oxford and beyond.

With the images of our past in mind, we should reject those who rely on remnants of the past and instead work toward the future – the future that those forgotten resisters envisioned.

Liam Nieman is a sophomore Southern studies major from Mount Gretna, Pennsylvania.