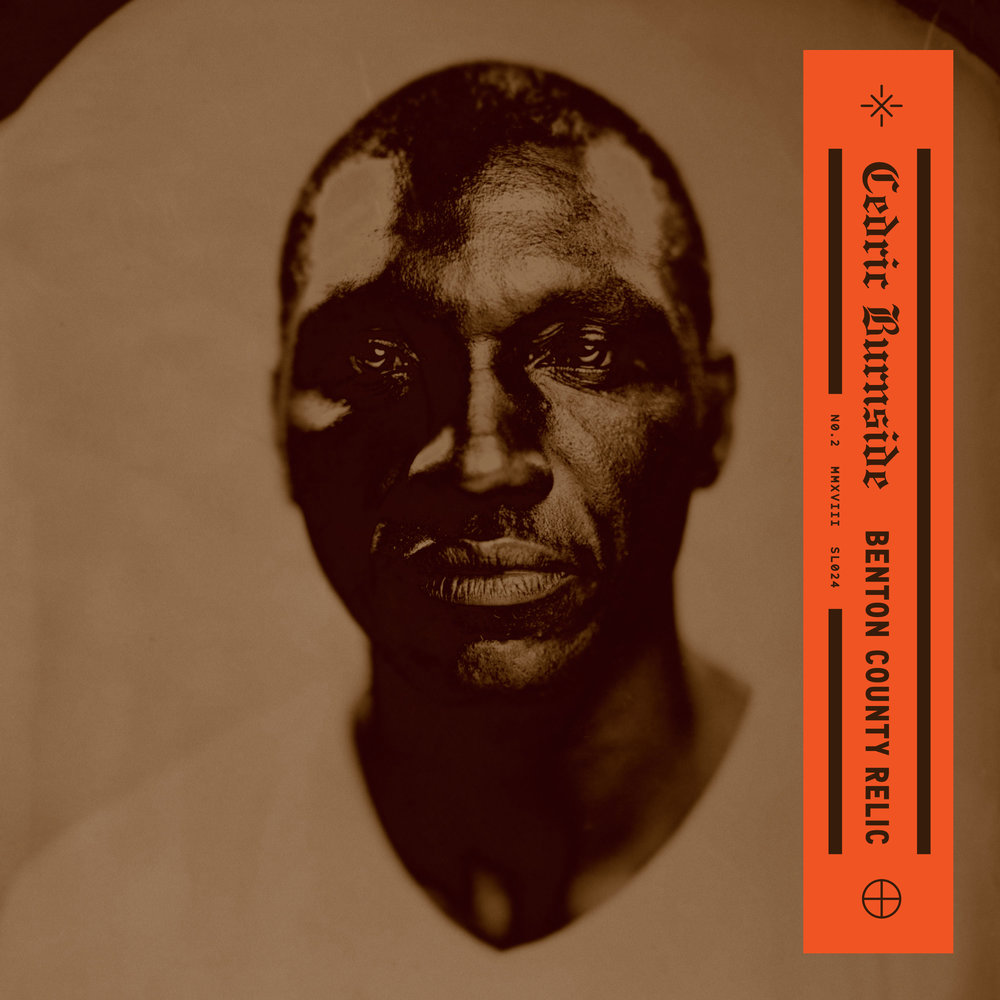

Called “Benton County Relic” and featuring a tintype portrait of the artist as its cover, Cedric Burnside’s latest album owes a lot to the past.

Burnside, who still lives outside of Holly Springs, was born in the thick of the blues. He’s the son of drummer Calvin Jackson and also the grandson of R.L. Burnside, a guitarist and singer whose name is practically synonymous with the North Mississippi hill country subgenre of the blues.

Some of the lyrics on September’s “Benton County Relic” give a glimpse into Burnside’s childhood, such as these ones on “Ain’t Gonna Take No Mess.”

“My school was a juke joint / from a kid ‘til I was grown / and blues is really / all I’ve ever known.”

Photo Courtesy: Single Lock Records

On “We Made It,” Burnside sings about how his family didn’t have much money growing up, even detailing how they would have to walk every day to get water for the house since they didn’t have a bathtub. But, as the title suggests, he and his family “made it” and got out of that intense poverty.

Like the music of the Hill Country artists like R.L. Burnside and Junior Kimbrough before him, Burnside’s music shines with the same hypnotic and rollicking instrumentals. Burnside’s steady, hard-hitting drumming combined with droning guitar riffs mimic the time-disintegrating quality of hill country live performances, where songs are often extended to over 10 minutes but still captivate the audience.

Though none of these songs go much longer than five minutes (besides the album’s weakest song, “Hard to Stay Cool”), it’s still easy to lose sense of time in the middle of “Benton County Relic.”

But despite its historic title, cover and influences, “Benton County Relic” is an album that also looks to the future sonically, lyrically and thematically. Burnside forges a new sound in the blues genre, a project continued from his 2015 Grammy-nominated album “Descendants of Hill Country.”

Like that previous album, “Benton County Relic” is crisply produced, unlike the gritty albums of Kimbrough and R.L. Burnside. Songs like “We Made It” and especially the rocking finale “Ain’t Gonna Take No Mess” bear just as much of an influence from rock ‘n’ roll as blues had on rock in its early days.

Bluesmen have almost always dealt with their relationships with women in their music. But unlike the antiquated, at-times-exploitative views of women that older bluesmen — even Burnside’s forebears — espoused, Burnside moves to a more nuanced views.

While he retains the sexy physicality that marks much blues music on such songs as “Give It to You” (“The way you shake your body / look good to me / I wanna give you / what you want and need”), songs like “Don’t Leave me Girl,” where he sings about waiting until after work to hear his partner’s stories, reflect this different viewpoint.

At times, this album, so infused with the past, zooms into the future.

“I think the blues / kept me alive / and I’m gon’ play / until the day I die,” Burnside sings on “Get Your Groove On,” suggesting the blues have a long way to go until they are “dead.”

Outside of its religious contexts, the word “relic” has two conflicting meanings. It is a remnant of the past, which can be either admired for its historical significance or seen as outdated, unnecessary. But the “Benton County Relic,” whether the album or Burnside himself, is definitely the latter — a gem left from a past era that still wields influence over the present.