On a journey to Mexico’s Oaxacan coast, Luisa, the young narrator of Chloe Aridjis’s “Sea Monsters,” puzzles over the French poet Charles Baudelaire’s “Un Voyage à Cythère.” By the end of the novel, with hundreds of miles of travel now behind her, Luisa thinks she has cracked the poem.

Luisa concludes that Baudelaire seems to say that “to imagine travel is probably better than actually traveling since no journey can ever satisfy human desire; as soon as one sets out, fantasies get tangled in the rigging and dark birds of doubt begin their circling overhead.”

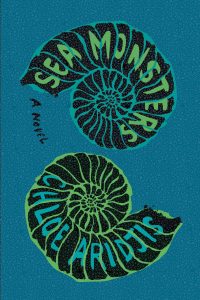

Photo courtesy: Amazon

What Baudelaire and Aridjis are getting at is the truth of Luisa’s — and, perhaps, all young people’s — journeys. Luisa sets out for escape, anonymity and adventure, but the places and people she runs from get in the way.

Set in Mexico in the 1980s, “Sea Monsters” opens with 17-year-old Luisa wandering on the beach in Zipolite “in search of digressions.” A few pages later she divulges that she is “here with Tomás, a boy I hardly knew, in search of a troupe of Ukrainian dwarfs,” although we still don’t know much about how she got here.

The narrative then jumps back to Luisa’s life in Mexico City. She lives with her family and goes to high school in the middle-class neighborhood of Roma, though she begins to slip, led by Tomás, into unfamiliar parts of the city — wrestling matches, nightclubs, the house where Beat Generation author William Burroughs murdered his second wife.

Then, after reading a newspaper story about the Ukrainian dwarfs, Luisa convinces Tomás to take a bus with her across the country in search of these mysterious circus runaways. From there, the novel becomes a repetitive cycle of Luisa’s days, spent wandering the beach, and nights, spent mingling with a mysterious “merman” at a local bar.

Throughout the novel, we learn far more through Luisa’s narration than we do about the facts of her life. For instance, we discover that Luisa is fascinated by human activity, picking up on a daily schedule of life that coincides with nature.

“In Oaxaca,” Luisa notices, “dusk was announced not by the tamalero, nor by the cobalt blue ceding to molten orange, but by the coral man, who would come into view just as the sun was departing” to sell necklaces and chunks of coral.

Moments like that one, which draw on memories and perceptions personal to Luisa, dot the slim novel. Aridjis trusts us as readers to follow along, filling in the gaps and accepting the obscure references to everything from Baudelaire to punk music.

“Sea Monsters” is unconcerned with plot, meandering just as much as its narrator. This is risky — we are breathlessly close to Luisa herself but distant from so many parts of her. But, at the novel’s end, looking back on the expedition with Luisa, we realize a journey can be transformative even when it ends in the same place it began.