Negro Terror has a lot to be angry about. Rico, the guitarist for the Memphis hardcore band, explained this anger in an interview for the new feature-length documentary about his group.

“You got the being black in America anger, then you’ve got the being different in black America anger and then you’ve got everything, just life in general anger, all that bullshit,” Rico said in the interview. “You mix all that up, you’re gonna end up with some shit like Negro Terror.”

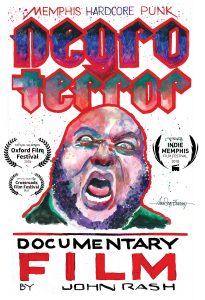

The documentary, directed by John Rash of the Southern Documentary Project, made its Mississippi debut last night as part of the Oxford Film Festival.

“Negro Terror” won the Soul of Southern Film Award at the 2018 Indie Memphis Film Festival, has both a live version — in which the band plays the film’s score in-person — and a theatrical cut. The theatrical cut screens at 5:30 p.m. Sunday on Malco Screen 2.

Along with their hardcore roots, Negro Terror draws influence from reggae music and the American Oi! Scene. The band consists of Rico, Ra’id and brothers David and Omar Higgins.

Although Negro Terror’s attention-grabbing name is the first thing most people notice about the band, the name is about more than just shock value. It came to Omar one night as he was watching an old serial TV show. A white announcer criticized rock ‘n’ roll music, eventually declaring the genre “Negro Terror music,” and Omar said, “That’s it.”

Negro Terror is an attempt to reclaim this language originally used to vilify black art and actions.

“Everything from the name, to the logo, to the history of the band, to just the members of the band itself was a concept that was, one, needed and, two, is very historical at its root,” Ra’id explained in the film.

Rash noticed the name, too, while looking for things to do in North Mississippi shortly after moving to Oxford. He felt like a concert with a band named Negro Terror could either be the worst or best thing he’d ever attended.

While doing some cursory research on Google, Rash found a YouTube video of Negro Terror’s cover of “Invasion” by Skrewdriver, a white supremacist band. The band members inverted the original song’s politics and overlaid their version of the song with images of the Holocaust, police brutality and Black Lives Matter protests.

Memphis hardcore band Negro Terror plays at Proud Larry’s on Wednesday night, accompanying a screening of their namesake documentary directed by John Rash of the Southern Documentary Project. Photo by Jeanne Torp

When he saw that video, Rash realized Negro Terror had a story to tell. He thought he’d go to a show or two and make a short documentary.

“After meeting them, I knew it would be a good short film,” Rash said. “What I didn’t know is that they’re such interesting and layered individuals that it became a feature-length film just because of how much content was there.”

Political Problems

But as Rash’s project expanded, limitations emerged. Because of the band’s uncompromising anti-fascist politics, its members asked Rash to film them only at select places and times, mostly before or after shows so as not to endanger anyone in their families or at their workplaces.

Omar, who has been an anti-fascist skinhead for 23 years and fought against “racism on all fronts” with the group Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice (SHARP), said that although he is not an extremist or a communist, far-right groups have labelled him as such. Neo-Nazis have harassed him online and published his personal information on far-right websites like Redwatch.

“We’ve got to lay low, but we’re still walking and talking,” Omar said. “A couple scares, a couple of threats aren’t gonna stop us — end of story.”

For decades, the skinhead subculture has been split into political factions and riddled by a wide range of negative stereotypes. But to Omar, it makes no sense for someone to be both a white supremacist and a skinhead.

“If you are a white nationalist and you call yourself a skinhead, that’s an oxymoron,” Omar said. “You’re talking about a subculture that developed from black people, Jamaicans … and reggae.”

Even though the extent of Omar’s activism stretches far beyond Negro Terror, Omar stressed that simply playing rock music as a black group is a political move.

“Rock ‘n’ roll is all it is,” Omar said. “There’s no black power, shock value, anything. It’s just rock ‘n’ roll, and if that isn’t a political push then I don’t know what is”

Rash said that accommodating the band’s requests didn’t negatively affect the final product.

“That limitation ended up being an interesting part of the film because most of it takes place in the environments where you would see Negro Terror,” Rash said. “I love that the backgrounds are patio walls and the backrooms of the clubs they play in.”

The Film Itself

From October 2017 to April 2018, Rash followed the band’s tour schedule, making regular trips to Memphis. He was also there in Jonesboro, Arkansas, in November 2017 when Negro Terror played its first out-of-town show.

During filming, Rash noticed that the crowds coming out to see Negro Terror were surprisingly diverse for hardcore shows. Rash compared the Negro Terror shows, which were “if not 50-50, majority African-American punk kids,” to the hardcore shows he attended while growing up in North Carolina, which were “70-percent white.”

Omar echoed Rash’s observation and said this diversity is a point of pride for the band.

“When we played our first show in 2016 (after a Black Lives Matter protest on the I-40 bridge in Memphis), kids started going, ‘Holy shit, there’s an all-black band out here, playing heavy shit,’” Omar said. “Then black kids started showing up and Hispanic kids and Asian kids.”

The diverse fanbase also had to do with the rap and hardcore scenes gelling together in Memphis’s musical environment. Both genres, Omar said, “came from the streets” and continue to be about working-class people.

Hannya Chaos, a Memphis rapper, was interviewed in the film because he has performed with Negro Terror before, and he pointed out the same connection.

“My music in particular is very aggressive,” Hannya Chaos said. “It has a lot of punk and rock elements to it, but, really, the message I spit is the same as in a lot of punk songs.”

Just as much as Memphis has changed American music and these musicians, the documentary is about Memphis itself changing. Much of the film’s b-roll footage consists of shots of a Memphis cityscape in flux: the freshly renovated Civil Rights Museum, gentrifying neighborhoods and neon lights downtown.

“My goal was to go there and let (Negro Terror) introduce me to what Memphis means to them because there’s a lot of stereotypes about Memphis, but Memphis has many different faces,” Rash said.

One of those faces is Beale Street — Memphis’s answer to Bourbon Street with a soundtrack of blues rather than jazz. While Rash shows Beale Street in the film, he hopes viewers take away more than just that already famous image.

“What I hope that you see is more a sense of the community,” Rash said. “Memphis really is a place that is a very artistic and creative community of people who are trying to help each other out.”

Going Live

It wasn’t until after editing the theatrical cut that Rash imagined a live version of the film. When he proposed it to the band, they accepted. Rash spent a few weeks recutting the film, and they presented this version for the first time in Memphis.

“(The band) put a lot of trust in me to make it something that didn’t reflect negatively on them,” Rash said. “And I also put trust in them because they got to decide where they play. We both got to release a lot of control to each other, so it truly became collaborative.”

The show last night at Proud Larry’s was their first time presenting the live documentary at a rock club. Rash said this allowed them, for the first time, to bring the film into a place it otherwise would not be.

Referencing “all the insanity” of Mississippi’s history, Omar said he hopes people will go beyond enjoying the music and tolerating each other to truly embracing others.

“It‘s one thing to tolerate someone, but there’s no love there. I don’t like that term,” Omar said. “We want people, even though it sounds cliche, to truly come together and learn something. We educate them, try to break it down for them.”

Starting in May, Rash and Negro Terror will bring their live show to houses, clubs and theaters along the East Coast. The tour will coincide with other projects for both of them.

That same month, Negro Terror will release its first album, “Paranoia.” Rash is currently working on two films: a profile of the Chinese-American photographer Sam Wang, who is based out of Clemson, South Carolina, and a historical film about the environmental justice movement’s North Carolina roots.