Students and faculty gathered in front of the Pavilion on Tuesday afternoon, some standing, some sitting in chairs and some sitting right on the ground, all listening to the individuals holding a book and a microphone read their favorite poems by Native American authors.

This event, titled “Itimanupoli” from the Choctaw word meaning “to converse,” was organized by Caroline Wigginton, associate professor of English and director of undergraduate studies for the department, as a way to kick off Native American Heritage Month, celebrated in November.

“Much of the energy, for a lot of reasons, has been around race and history and ethnicity around African-Americans and white people,” Wigginton said. “This means that here in particular our Native American populations are hidden.”

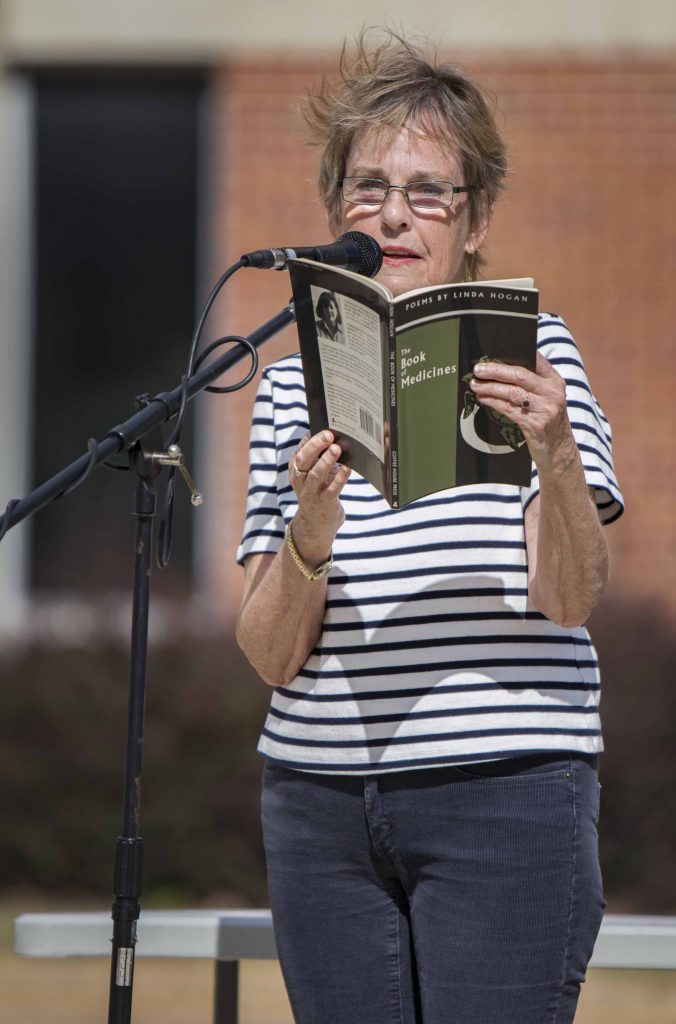

English professor Ann Fisher-Wirth reads poetry by Linda Hogan, the Chickasaw Nation’s Writer in Residence, on Tuesday. Photo by Christian Johnson

English professor Ann Fisher-Wirth chose to read a poem by Linda Hogan, the Chickasaw Nation’s writer in residence. She read the poem “The Harvesters of Light and Water” from Hogan’s book “The Book of Medicine.”

“I love Linda Hogan’s work. She’s a novelist and an essay writer and a poet and she’s a dear friend of mine,” Fisher-Wirth said. “She’s such a lyrical, grounded, loving and fascinating writer.”

Aimee Nezhukumatathil, professor of English and creative writing, chose a poem by Natalie Diaz, an author of Mojave and Latinx decent, titled “From the Desire Field,” for a very specific reason.

“I wanted to choose a love poem. I wanted to choose a desire poem,” said Nezhukumatathil. “Not very often do you see women of color depicted as experiencing love or lust.”

Poems by several other authors, including Qwo-Li Driskill, a mixed-race, queer member of the Cherokee Nation, were selected and read aloud. The event highlighted the diversity and continued vitality of Native American populations across the United States, allowing students to better understand the experiences of the poets and the context in which the poems were written.

Sophomore English and political science double major Joshua Mannery said it was good to see the poems in their broader context. One poem was written in response to President Barack Obama’s American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, which includes funding for Native American housing and the settlement of the Keepseagle Case, which centered around the allegation that the U.S. Department of Agriculture had discriminated against Native Americans in its loan programs.

Mannery said he was able to relate to the works more than he had anticipated he would.

“I didn’t know what kind of style they might have, but it was really familiar to me for some reason,” Mannery said.

Wigginton said she organized “Itimanupoli” to help students understand the modern experiences of Native American populations.

“(Mississippi has) a federally recognized nation, (and has) ties to removed nations that are in present day Oklahoma, but nevertheless these populations are invisible,” Wigginton said.

The Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians is the only Native American tribe federally recognized in Mississippi. According to its website, there are currently 10,000 members of the tribe, and its lands span across ten counties, covering 35,000 acres.

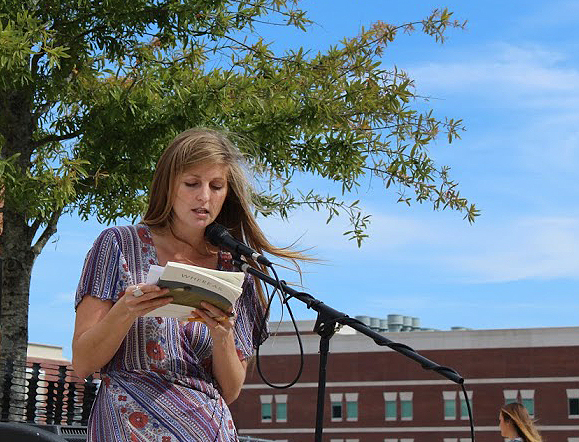

Amy Erwin reads poetry by Layli Long Soldier during the Native American poetry reading Pavilion Presents event on Tuesday. Photo by Haleigh McNabb

Other tribes who historically lived in Mississippi — the Biloxi, Chickasaw, Houma, Natchez, Ofo, Quapaw and Tunica tribes — were forced out of Mississippi in the nineteenth century during the era of Indian removal. These tribes are now primarily located in Oklahoma and Texas.

To conclude “Itimanupoli,” Wigginton asked the audience to join together in saying “Yakoki,” meaning “Thank you” in the Choctaw language. She reminded the audience how long the Choctaw people took care of the land Mississippians now use.

Students can visit the Center for Inclusion and Cross Cultural Engagement’s website for information on upcoming events to celebrate Native American Heritage Month.