Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article incompletely described the revenues and expenditures for the education and general enterprise fund on the Oxford campus. The original version did not distinguish that fund from the university’s total revenues and expenditures.

In a decades-long shift in who funds the university, state and federal governments now pay far fewer bills than they once did. Students, especially nonresidents, now pick up much of the tab.

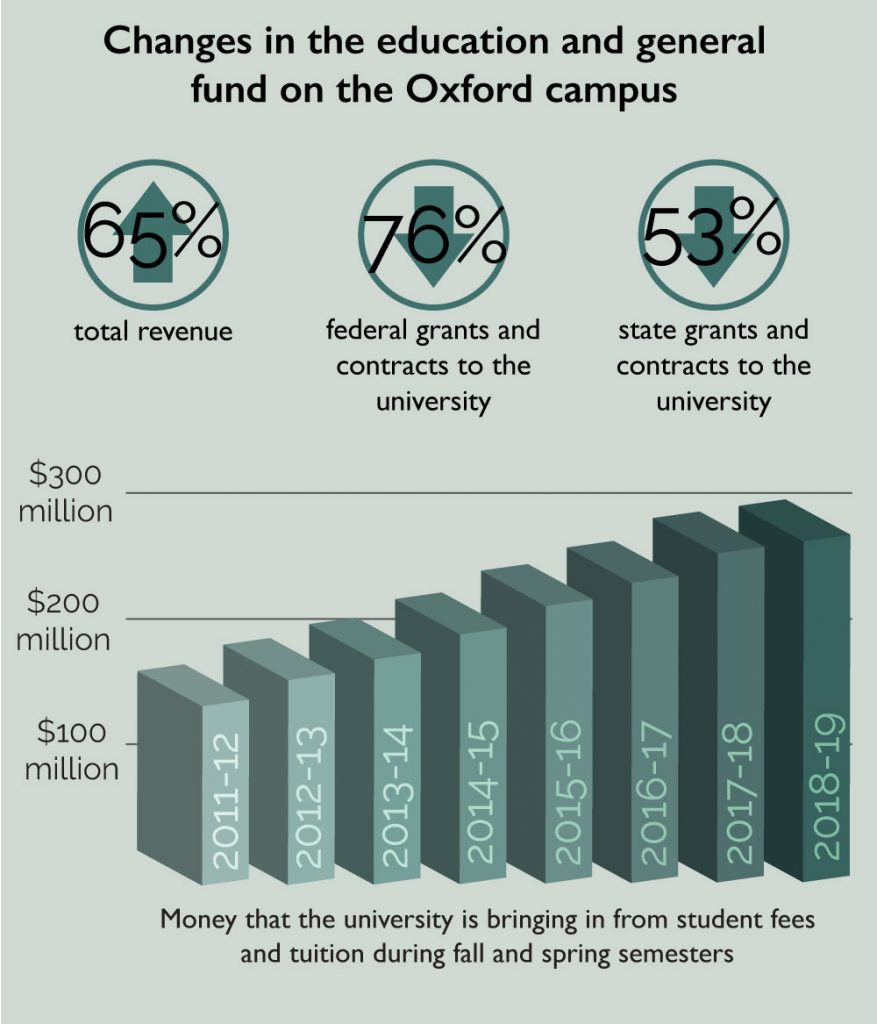

Out of the $540 million that Ole Miss had budgeted to spend from the general and education fund on campus last school year, $285 million came directly from students in the form of tuition and other student fees. Nearly 40% of that $285 million comes from nonresident fees.

Interim Chancellor Larry Sparks said that these funds are crucial to the sustainability of the university.

“(Students are) the lifeblood to keep our doors open,” he said.

The trend of student dependency isn’t unique to the University of Mississippi. All over the country, government funding has decreased overall. For Ole Miss, state appropriations have dropped in the general and education fund on campus — over $11 million since the 2015-2016 fiscal year.

Sparks, who served as vice chancellor for administration and finance before becoming interim chancellor, added that he doesn’t think that higher education’s current business model is sustainable.

“Universities are on one side of the fence on being more like a business, if you will, in terms of trying to remain financially viable and provide top-quality education,” he said. “On the other side of the fence, they have a foot in government regulations in terms of how to picture things (and) hire people. That is more inefficient. So we’re trying to serve both masters.”

As public universities’ playing field for recruitment becomes more competitive to bring in student dollars, pressure is put on universities to keep up certain amenities and programs that keep prospective students returning to their campuses.

“When I came to school, we didn’t have orientation. We didn’t have Junior Day visits,” Sparks added. “I mean, those are products of what’s required now in terms of the recruiting of the next class’s students. But within that, there’s a competition with scholarships. Those are highly competitive, and we cannot continue to increase scholarships, the dollar values and the breadth of those, endlessly.”

Sparks, who has spent 35 years working in higher education, said he remembers when “the lightbulb went off” in his understanding of how higher education worked financially — as an auditor in the 1980s. He was tasked with auditing universities alone, and though that caused a lot of stress, he said, he wouldn’t trade the experience for anything.

“Things clicked in terms of how things fit together,” he said. “You start visualizing things and you start realizing things that you didn’t previously, and really the area of cause and effect, you know that if something happens in this area, there’s an unintended consequence here and here, or you’ve got to keep these things in mind.”

Graphic: Katherine Butler.

And as the total revenue available for spending in the education and general budget on campus has grown steadily from $327 million in 2011 to a whopping $540 million for this past school year, eyes of administration are looking toward expansion and growth. Student fees are not the only place that the university is looking for revenue as government support declines. Donations are being used to fill in the gaps as well.

Donors often give through the University of Mississippi Foundation, either to endowment or non-endowment funds.

The $725 million endowment is invested in markets and the return — often 5-10% per year — is used by the university. As it grows — as it did by over $100 million in 2018 — the return grows. The fund has consistently outperformed endowments of similar sizes.

The UM Foundation is “like the bank” to UM, according to UM Foundation President Wendell Weakley.

With shifting sources of revenue, donors have increasingly become a source of money for the university to offset costs. Donor money, though, is often earmarked when it is given.

“It’s very rare that someone gives a gift and says ‘put it wherever you want it,’” Weakley said.

Many donations are directed toward a particular school, scholarship or need, which leaves some costs without offsets. Student fees and government funding often fills in the rest.

The foundation also takes the needs of deans and individual schools into account when they are fundraising. The specific needs of the university are used to direct campaigns to direct donations.

“I suspect we’ll be in campaign mode before too long,” Weakley said, mentioning that he thought a new accounting building, Ole Miss Opportunity scholarships and faculty funding would be the focus of future campaigns.”

By putting money toward costs that will already have to be paid in the future, donations help “relieve the pressure of the operating expenses of the university,” he said.

Weakley said that the UM Foundation, as well as the university as a whole, is in a good financial position today — despite changing sources of revenue — because the foundation was anticipating the future in the 2000s.

“The next chancellors are going to be very glad that you’re making these calls,” Weakley told former Chancellor Khayat as they contacted donors.

Today, UM and the UM Foundation look to the future again, expanding fundraising departments and planning for future decades. Specifically, the UM Foundation is focusing on the transfer of money from the Baby Boomers to their benefactors. A new position was created to encourage donors to include UM in their will after their death.

“We want to make sure we’re part of that (wealth transfer),” Weakley said. “Those are gifts we’re not going to see for 15 to 20 years. But in 15 to 20 years, we’re going to be very happy that those calls were made.”

As the university anticipates financial growth, it plans for its distant future.

In 2017, the university updated its “Master Plan,” a flexible blueprint of how UM’s Oxford campus will develop in the future.

While the elements in the plan aren’t set in stone, this document is used as a reference for upcoming projects, such as when it was used in choosing where to begin construction of The Pavilion.

“The Master Plan is not something that has an end date, nor does it have a conclusion,” Sparks said. “Nor is it written in stone. This is how things will occur. It grew, and, in our case, from rapid growth.”

He also said that many of the university’s expansions are currently being planned, though the final decisions won’t be made for several years.

“And as we’re growing, we need to be thinking about and planning for that growth,” Sparks said. “What types of facilities? What about transportation? What about utilities? We need to have, in our minds, thought about certain needs.”

Though a lot of Ole Miss’s new leadership, including the choice of having star-fundraiser Keith Carter as Interim Athletic Director, has been centered around the financial world, Sparks said he doesn’t subscribe to the theory that finances dictate administration.

“I’ve had the pleasure of working here for 22 years, and I think I have a lot of institutional knowledge,” he said. “And in a period, I think that’s very helpful in terms of having someone that doesn’t have to make new relationships and gain the confidence and build those relationships in order to get things done, or to even figure out who I need to go to in order to get to have those conversations.”