James Meredith, the university’s first black student who enrolled in 1962, expressed a change of heart on two issues following an emotional weekend. The civil rights icon said he’s become more receptive to his statue as well as to the school’s Black Alumni Reunion.

“This is really a time for change in me and in what I’m going to do,” Meredith said. “I really, from this weekend, have promised God that I would conduct my life in a different manner than I ever have before.”

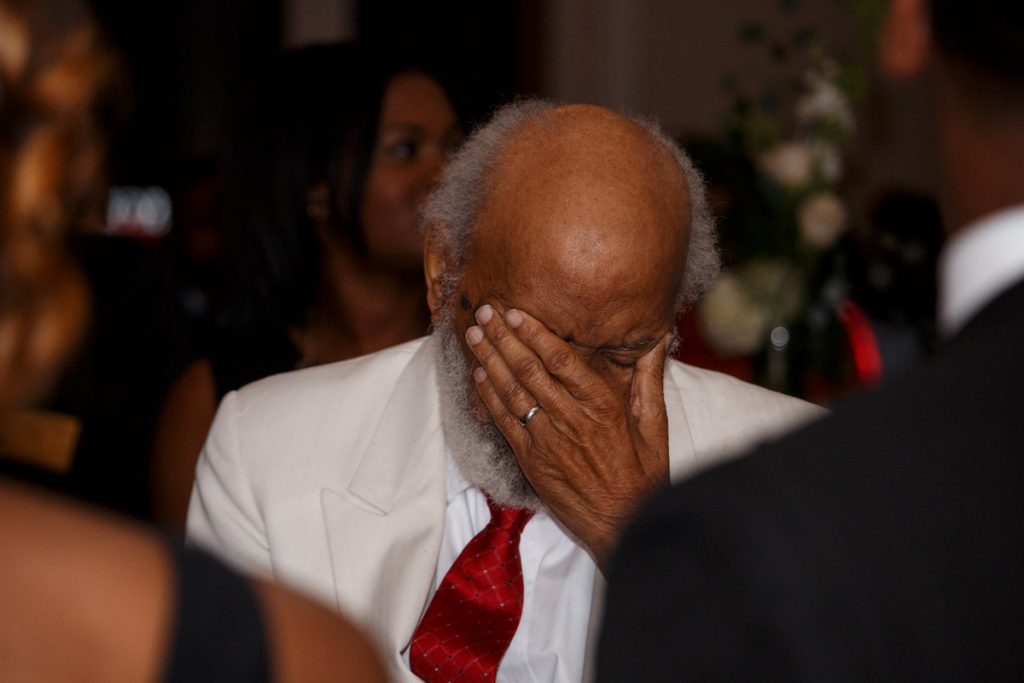

James Meredith reacts to a video honoring the advancement of African American students at the University of Mississippi during the Black Alumni Reunion Awards Gala Saturday night. Meredith was the first African American to attend Ole Miss, admitted in 1962. Photo by Billy Schuerman

He said this change was brought about thanks to this weekend’s Black Alumni Reunion, an event honoring the university’s African-American graduates that takes place every three years. This year, the Black Alumni Reunion honored Meredith for the first time since the event’s conception in the 1980s. The prior absence of his recognition was partially because of Meredith’s resistance.

“I fought it for at least 30 years, just like I fought the statue,” he said.

The statue he’s referring to is one created in his own likeness. It’s nestled between the Lyceum and the J.D. Williams Library. The statue has gotten a lot of attention since it was placed there, often as a spot for students to socialize but sometimes as more. It’s been a place of conversation for one student who sat there displaying inspirational quotes on posters and encouraging passersby to start dialogue every day during the years he attended classes. Another time, a few white fraternity members were expelled after placing a noose and Georgia state flag containing the Confederate battle emblem on the statue in 2014.

Meredith has vocally opposed the statue since its unveiling in 2006. For 12 years, he has advocated that the solution to the university’s racial tension was to tear down both his statue and the Confederate soldier statue that sits at the front of the Circle.

The James Meredith statue on the University of Mississippi campus. (File photo)

“I’ve been telling (the) chancellors, ‘Take that statue down and take the Confederate statue down and we’re going to solve both problems.’ After this weekend, I know that ain’t the way to solve it. I understand that,” Meredith said. “And the way Ole Miss has been going about it, I think is more wise than anything I had in mind.”

Meredith said his change of heart is thanks to this year’s Black Alumni Reunion.

“This is the only one I’ve attended, and I’m very glad I did,” Meredith said. “As a matter of fact … I’m going to go look at the statue behind the Lyceum for the first time since they put it up.”

Many reunion attendees echoed the same phrase to Meredith all weekend: “We stand on your shoulders.”

Meredith said he’s received praise since he first walked on the Oxford campus in 1962, even amid the hatred and violence he faced at the time. He admitted he’s always struggled to understand why the decision to attend the University of Mississippi was so important to so many people.

“I’ve been hearing this for the past 50 years, since I first went here, but today was the first time I ever understood it,” Meredith said.

James Meredith, the first African-American student admitted into Ole Miss, speaks about his experience as a student in Oxford during the “Alumni Experiences Through Decades” panel Saturday morning, a part of the Black Alumni Reunion. Photo by Logan Conner

Meredith said he picked Ole Miss not because he wanted to tear down racial barriers but because of the success associated with the university’s graduates.

“I had observed in Mississippi that people that went to Ole Miss and went back home in their community always dominated everything,” Meredith said. “And I noticed particularly that that is not happening with the blacks who went to school.”

Dexter Foster helped create the Black Alumni Reunion in the 1980s and served on its committee this year. He said the reunion is important to alumni and students for networking.

“One of the main purposes to have the Black Alumni Reunion was to bring black students and now alumni back to the campus to see the growth and bring back active participation to support the black students,” Foster said.

Foster said Meredith’s experience and enrollment in the university made events like the Black Alumni Reunion possible.

“It’s good to see James Meredith. It was good to give him the award,” Foster said. “He’s never been recognized during any of these events and he’s exactly the person for these events.”

Judy Meredith, journalist and James Meredith’s wife, said she enjoyed the event because it recognized the importance of alumni vocalizing their victories and struggles.

Ole Miss alumni James Meredith (left); Nic Lott, the first African-American student body president at UM (middle); and Teresa Jones, current Deputy Executive Assistant to the Democratic Minority Leader (right), discuss their experiences as a student at Ole Miss during the “Alumni Experiences Through Decades” panel Saturday morning, a part of the Black Alumni Reunion. Photo by Logan Conner

“It’s important for them to remember and to talk to each other … to laugh, talk, tell any war stories they may have,” she said.

Upon the weekend’s conclusion, Meredith said he is quick to scrutinize the university’s network of alumni and students because it is broken.

“Networking ain’t exactly what Ole Miss is about,” Meredith said. “Ole Miss is the good ol’ boy system. It’s more than networking.”

He said the reunion is a step in the right direction for opening up that “good ol’ boys” club.

“I know that really has helped, because if the university wasn’t doing what it’s doing … black education would not be near where it is,” Meredith said.

After decades spent criticizing the university for its race relations, Meredith commended the University of Mississippi for prioritizing black alumni.

“Ole Miss saw what I’m seeing,” Meredith said.