“My only son, William Scott Smith, decided to leave this world on May 3, 2015.”

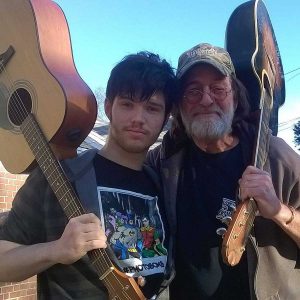

His story starts unassumingly, like any other. He had a loving mother, a band of misfit buddies and a talent for playing guitar.

But digging a little deeper, one would find a boy whose depression and anxiety quickly spun him into a web he couldn’t untangle. He spiraled, finding solace in joints and cigarettes in his backyard treehouse — until, one day, he climbed up the tree to escape for the last time.

His loving mother hasn’t sat down since.

Pam Smith, a senior collections assistant in the Office of the Bursar, has worked tirelessly for the past two years to raise awareness for suicide prevention in memory of her son. A board member of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention for the state of Mississippi, a co-organizer for Oxford’s Out of Darkness Walk for Suicide Prevention and a full-time employee of the university, Smith is known for her passion and willingness to share her story, as personal as it may be.

It didn’t happen all at once, Pam said. When Scott became a teenager, she said he adopted “semi-gothic” traits.

“He wanted to paint his nails black, but I didn’t let him do that,” Pam said with a grin.

His self-expression flourished as he got older, and his relationship with his father began to change.

“I told his father that just because we lived in Mississippi, he didn’t have to be a country boy,” Pam said. “They have the same temperament, and one day, they actually got into a fist fight.”

His father moved out, and Scott’s behavior deteriorated. Pam began to notice the smell of marijuana coming from his bedroom. Shortly after, she received a call from Scott’s school saying he’d been expelled after officials found a joint in his backpack.

“If you want a pain in your heart, go to the sheriff’s department to pick up your child,” she said.

And that’s when Scott broke down. When they got home, Scott told her he needed help, and Pam sprung into action. She had him admitted to Parkwood Behavioral Health System, a psychiatric hospital in Olive Branch, where he was held on suicide watch for three days.

“While he was there, I locked up everything in the house, even ibuprofen,” she said. “I cleaned out everything in his bedroom and treehouse. I found so much, you know, paraphernalia.”

After insurance stopped covering Scott’s stay at Parkwood, he was forced to stay home alone all day as Pam worked. She tried to get him re-enrolled in school, but the superintendent refused.

Regardless, Pam kept pushing. She bought him a GED study guide, and Scott agreed to enroll in training at Camp Shelby. Things seemed to be looking up, but Pam later found out the progress was only surface-level.

On the morning Pam will never forget, Scott was in a good mood. He was making strides with his guitar-playing and had just created a new band. Pam decided to cook Scott’s favorite meal, fried steaks and gravy, and he happily agreed to eat dinner with her before he headed upstairs. When he came back down, though, his mood had changed entirely.

“By the time I got through, he just had this different look on his face,” she said.

Scott and his girlfriend were fighting, and he told his mom casually, “I’m going to walk around Harmontown. I’ll be back later.”

Pam asked him to stay, but before she knew it, he was out the door.

Scott’s curfew was 10 p.m., and when Pam woke up in the morning, she expected to see him sleeping on the couch as he usually did on nights he came home late. But he wasn’t there.

She looked around town all day and called his friends, but no one seemed to know where Scott was. It wasn’t until hours later that it dawned on Pam that he might be in his treehouse.

“That’s where I found him.”

For months after that day in May, Pam was living her nightmare. She grieved. She cried. She screamed at the sky.

“I was just numb,” she said. “He was my only son. I’m never going to accept it.”

At the funeral, her son’s friends told her, “Our person is gone. What are we going to do?” And that’s when she finally understood that, even though she might never be able to accept it, he was called home for a reason.

“I realized then — my son was a counselor. He spent so much of his time helping other people,” she said. “I do believe that maybe God needed a counselor up there with him in heaven.”

The thought comforted Pam and helped her through the darkest of times. Scott was a listener and confidante, taking on the problems of his closest friends as his own, without regard for himself. Scott was outgoing and loving. Because of him, Pam’s house was always full. He was a person who naturally and genuinely loved and cared for others, and he got it from his mom.

Pam used grief to fuel her passion for suicide prevention. She joined the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and is now a board member. With AFSP, she has raised money, spread awareness and helped pass bills. She has sent letters to senators and the president of the United States. Pam hasn’t stopped fighting and doesn’t plan to anytime soon.

“I found that it’s OK to cry,” she said about overcoming grief. “Now, screaming — I don’t know if that works or not.”

Even though Pam Smith lost her only son to suicide just two years ago, it’s hard to imagine her being sad. Maybe she’s just moving too quickly for anyone to tell.

She helped with Oxford’s Out of the Darkness Walk for Suicide Prevention for the past two years, and the chairman of the walk, Maddy Gumbko, said it wouldn’t have been nearly as successful without Pam.

“When I first met her, you could tell that she was really grieving. She has gained so much courage since,” Gumbko said. “Last year, she didn’t want to speak at the walk, but this year, she did.”

When she first met Pam, Gumbko had just lost a close friend to suicide and said that even though her interactions with Pam reopened painful, fresh wounds, they opened her eyes.

“It’s still just as heartbreaking, but Pam’s openness about her story made me realize that to be able to have conversations about suicide, we have to be able to talk about it,” she said. “She has such a passion and fire and drive to change the world and save lives in memory of her son.”

Pam hopes that by spreading awareness about the cause, her son’s legacy as a “counselor” can live on through her.

“This is an issue we don’t talk about enough,” Pam said. “By talking about it and making a personal connection with people, we can save more lives.”

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among teenagers and the 10th leading cause of death in the country. White males, like Scott, accounted for 7 out of every 10 suicides in 2015, and those numbers are climbing.

Statistics like that are why Kathryn Forbes, president and co-founder of the Ole Miss chapter of Active Minds, a national organization that promotes mental health awareness and education on college campuses, is bringing light to suicide awareness and prevention here at the university.

“One in 4 college students struggle with mental illness. It’s so important to be open about it so people know they’re not alone,” she said. “I love how open Pam is about her story, because the more open you are, the more people will come up to you and tell you that they are suffering, too. We need to have these conversations to reduce the negative stigma around mental health.”

Pam recently got a tattoo on her forearm — a guitar with Scott’s name inscribed across the front.

“Scott wanted to get a tattoo, and I wouldn’t let him,” she said. “Finally, before he died, I told him that I’d get a tattoo with him, so this is for Scott.”

Pam imagines Scott still plays his guitar. He probably still smokes cigarettes, too, with his messy black hair across his forehead. But most importantly, she thinks he is still helping others, and as long as he is, she will be, too.