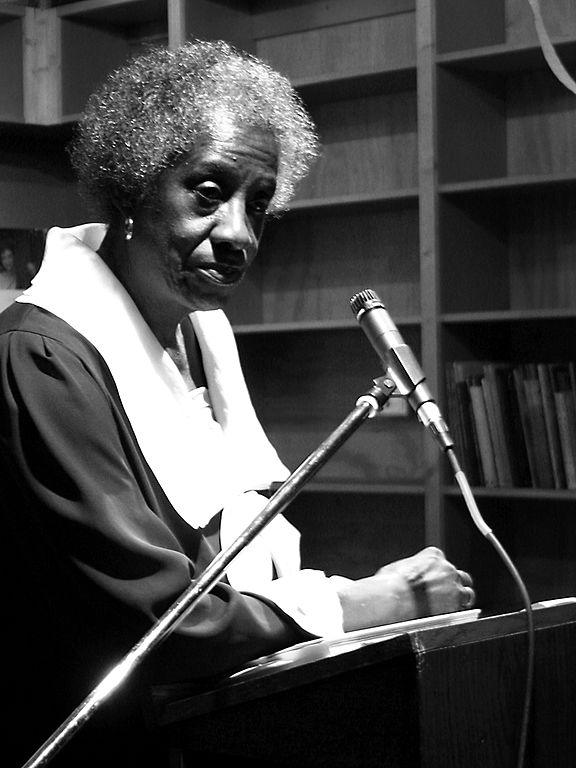

Unita Blackwell, the sharecropper who later became the first black woman mayor in the state of Mississippi and advised six U.S. presidents, died Monday at age 86.

Her son Jeremiah Blackwell Jr. told Mississippi Today his mother died Monday morning at a hospital in Biloxi after a long battle with dementia.

Blackwell was an important pillar in the civil rights movement in the South. She served as a project director and field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), helping organize voter drives for African Americans across Mississippi.

Those efforts landed her in jail at least 70 times, she said, for trying to register black Mississippians to vote.

“I was put into the position of learning to survive, someway and somehow, by being black and in this country,” Blackwell said in a 1977 oral history interview with the University of Southern Mississippi. “But also being black and in this country, you learn a great lesson, and this is how to overcome… It’s that power to move in the midst of opposition.”

During her life, she served as an adviser to Presidents Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton.

Born in Lula in 1933 into a sharecropping family, Blackwell left Mississippi as a child to attend school in West Helena, Arkansas, because black children weren’t allowed to consistently attend school at that time in the Mississippi Delta. As a teenager, she married and moved to Florida, where she worked in fields and odd jobs, like at a canning factory during certain harvest seasons.

She and her family moved back to Mississippi, settling in Mayersville in Issaquena County, in 1962 — as important years in the civil rights movement were on the horizon.

“Mississippi, you know, people want to know why we are still here and why do we stay here. But Mississippi is home,” Blackwell said in a 1986 interview with Washington University in St. Louis. “It’s a place where I was born, reared on the land. The land is important to us. It was, it was the mean of the hard work, but it, it made us angry, it made us happy, it made us all these things, you know, but we was connected with the land.”

Blackwell continued: “Because we as black people, in the state of Mississippi and especially in the Mississippi Delta, worked the land. We didn’t own the land but, but we worked the land and so everything was tied around this land. And I feel that that’s the reason why I love Mississippi. It’s ours.”

Almost immediately after she moved back to her home state, she began volunteering with voter registration efforts and met key activists in the state like Bob Moses, Stokely Carmichael, Aaron Henry and Ed Brown.

During the 1964 Freedom Summer, Blackwell was elected a member of the executive committee of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and traveled to Atlantic City as a part of the delegation — including Fannie Lou Hamer and Henry Sias — that served as an alternative to the all-white Mississippi delegation at the 1964 Democratic National Convention.

Back in the Delta, Blackwell never stopped working to expand voting and education rights for black Mississippians. In 1965, Blackwell, working with the Jackson NAACP, sued the Issaquena County Board of Education, which had suspended 300 students for wearing freedom pins. The case, filed after Brown v. the Board of Education, served as the basis for one of Mississippi’s first desegregation orders.

Blackwell testified before the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Employment, Manpower and Poverty during Sen. Robert F. Kennedy’s noted 1967 visit to Mississippi.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, she served for ten years as a community development specialist with the National Council of Negro Women.

In 1976, Blackwell was elected mayor Mayersville, becoming the first African American woman to serve as a mayor in Mississippi. She held the position for 25 years until 2001. While still serving as mayor in 1992, she was awarded the prestigious MacArthur Foundation’s Genius Grant.

“The power to move doesn’t care what the circumstances are, cause nothing goes right for us,” Blackwell said in the 1977 USM oral history. “Nothing is set up for me to be the mayor of Mayersville, Mississippi. Nothing has been laid out for me to be that, cause everything was against us, you see. But you learn how to move, no matter what.”

She continued: “And that’s what blows people’s minds, you know. I think that’s what blows the minds of the white people in this country around us because we do have certain kinds of cultures and different characteristics, and they say, ‘Well how do they do it? How did something bloom, just like that,’ you know. But it’s not just like that. It’s because that we have been through a process over hundreds of years in this country that makes us move through obstacles. And they didn’t have no idea, this society, what it was creating. It created slavery, but it also created a people that can live through any kind of crap, you know.”

Funeral arrangements are pending.