Four aging men sit around a booth at the Beacon. ItŌĆÖs late afternoon, and the steady drip of a slow Oxford rainstorm is tapping on the tinted windows of the oldest restaurant in town. The rain isnŌĆÖt louder than the hum of the conversation, which drifts from whoŌĆÖs really running City Hall to socialism and the conservative movement.

These four men donŌĆÖt need menus. They’re only interested in the usual.

The Beacon ŌĆö with its tattered leather booths and greasy linoleum floor ŌĆö is the quintessential Southern diner. Frozen in time, the Beacon offers a reprieve from the daily minutia of Oxford. These men come to the Beacon because the coffeeŌĆÖs always hot, the kitchenŌĆÖs never empty and the staff knows their names.

But their names don’t matter. They could be Dickie Scruggs or Samuel L. Jackson or Johnny Cash. For all of the BeaconŌĆÖs congeniality, itŌĆÖs anonymous as well. ItŌĆÖs where the power brokers of northeast Mississippi, framed by the bars and stars of Confederate flags on the dining room wallpaper, flesh out OxfordŌĆÖs problems over black coffee and ketchup-smothered bites of country fried steak.

Ed Meek sits in one of these booths. Not on this day, but on many days before.

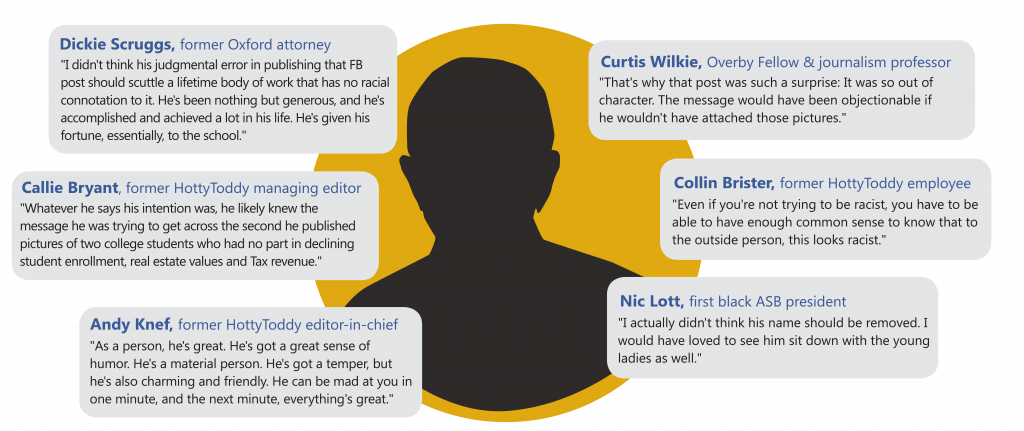

Overby Fellow Curtis Wilkie, a journalist and longtime friend of MeekŌĆÖs, jokes that conversations Meek regularly has at the Beacon were the influence behind the controversial Facebook post Meek shared in September that caused his name to be removed from the journalism school and his lifeŌĆÖs work to be tarnished.

ŌĆ£The problem is you spend too much damn time at the Beacon,ŌĆØ Wilkie said. ŌĆ£I said to Ed, ŌĆśPart of the problem is you spend too much of your time listening to a bunch of malcontents who think Ole Miss and Oxford are going to hell in a handbasket.ŌĆØ

He noted that the Beacon is a sacred Oxford institution, and in no way does he mean to defame the restaurant or its patrons. But his point is salient.

Meek is motivated by commerce. HeŌĆÖs a businessman in a journalistŌĆÖs world. Clicks are commerce for Meek, and no story is above reproach ŌĆö not even a listicle ranking cities by the attractiveness of the women who reside there: a story Meek pushed for.

WilkieŌĆÖs half-hearted assertion that Ed Meek is impressionable holds true among his acquaintances. Callie Bryant, a former employee of MeekŌĆÖs and one of his loudest detractors last fall, confirms this.

ŌĆ£He is a reactionary, first and foremost, and perhaps the very definition of him,ŌĆØ Bryant said. ŌĆ£He liked to be the first to say something. Perhaps he saw that extreme stories got extreme reactions. A click is a click ŌĆö no matter what.ŌĆØ

Following MeekŌĆÖs response to the removal of his name from the journalism schoolŌĆÖs edifice, Bryant tweeted, ŌĆ£This is right out of his playbook. Every time Ed kicked the hornetŌĆÖs nest heŌĆÖd play the martyr/victim/unwitting fool after.ŌĆØ

However, Bryant declined to say that Meek is a racist. She worked as an editor at HottyToddy.com, a news website Meek created, for more than two years and spoke with him nearly every day. Despite his erratic behavior, both publicly and privately, Bryant contended that Meek was a generous boss.

Several of BryantŌĆÖs co-workers and MeekŌĆÖs former employees declined to comment in fear of legal retribution.

Meek says heŌĆÖs not a racist, despite the content of his post. His friends agree, and so do his former employees ŌĆö though they acknowledge his complicity in sharing racist tropes on Facebook. Wilkie, who has known Meek since they were both freshmen at the university in 1958, does as well.

ŌĆ£In all of the years IŌĆÖve known him, IŌĆÖve never heard him use a racial epithet or say anything derogatory or anything at all that went into the Facebook post,ŌĆØ Wilkie said. ŌĆ£I think that was kind of an aberration.ŌĆØ

WilkieŌĆÖs an old-school progressive. Hanging in his office are framed covers of the Boston Globe ŌĆö where he worked for nearly 30 years ŌĆö a ŌĆ£Hunter S. Thompson for SheriffŌĆØ poster and biographies of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson: mementos of a foregone time as well as a window into his psyche. His politics are diametrically opposed to those of Ed Meek, but thatŌĆÖs never driven a wedge into their friendship. He said that Meek, as a conservative in Mississippi, is not some ŌĆ£old-school segregationist.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£That does not apply to Ed,ŌĆØ Wilkie said. ŌĆ£Ed wouldn’t be my friend if he were like that.ŌĆØ

Nic Lott was one of the first people to voice public support for Ed Meek during the fallout from his Facebook post.

Lott, elected in 2000 as the first black Associated Student Body president in the history of the university, counts Meek as a dear friend. He also doesn’t believe Meek is racist.

ŌĆ£I know that he was very disappointed and hurt that he had been labeled that and that his name was removed from the school. It really hurt him,ŌĆØ Lott said. ŌĆ£If somebody is really racist, they’re not going to be hurt by being labeled a racist. Ed was really hurt by that.ŌĆØ

Lott and Meek first met when Lott was a student at the university. Meek helped raise funds for the College Republicans and supported Lott in his campaign for the student body presidency. Lott has since worked as a political commentator on Fox and CNN and is running as a Republican for the office of commissioner of Mississippi Public Service.

Lott is a political ally to Ed Meek. Dickie Scruggs, OxfordŌĆÖs billionaire attorney and the only other living person to have their name removed from an Ole Miss building, is not. Scruggs is a liberal Democrat who was set to have a campaign fundraiser for the Hillary ClintonŌĆÖs presidential candidacy in 2007 before he was indicted on federal bribery charges. Like Lott, Scruggs supported Meek and disagreed with the removal of his name from the journalism school.

ŌĆ£It was more of a generational mistake than a racial mistake,ŌĆØ Scruggs said. ŌĆ£I think Ed would have put the same picture if it would have been two white girls dressed like that. But somebody sent him those pictures, he didnŌĆÖt take them. So, he just acted on what he saw, and it pressed a nerve.ŌĆØ

However, the narrative that Meek was simply reacting to pictures a friend sent him doesn’t line up with the facts.

As revealed by a public records request, 72 hours prior to his Facebook post, Meek repeatedly pressured HottyToddy.com CEO Rachel West to run with a story that women were engaging in prostitution on the Square and that fights were ruining Oxford. West demurred, and MeekŌĆÖs idea ended up in a Facebook post instead of the front page of a university-controlled publication.

Aside from an apology shortly after the post and a Facebook post expressing sadness that his name was removed from the journalism school, Meek has been silent for over six months. HeŌĆÖs declined all requests for interviews and has kept a low profile in the town where he was once lionized.

In private conversations, according to friends and colleagues, Meek conveyed astonishment that his Facebook post was perceived as racist.

Those same friends tell stories of Meek requesting funding for a primarily black church in Oxford. They tell stories of Meek assisting young black women in journalism land jobs after graduation. They tell stories of Meek convincing James Meredith to return to campus 30 years after the deadly riots that took place on campus when he tried to enter. They tell stories of an Ed Meek that is seemingly incapable of producing racist tropes in that fallacious 145-word Facebook post. But the words werenŌĆÖt the problem, the images were. And they are inextricably linked.

In a 2016 interview with Marshall Ramsey broadcast on PBS, Meek discussed the mindset he possessed as a teenager from Charleston, Mississippi, walking onto campus in 1958.

ŌĆ£I brought with me the same prejudices that we all had at that time. For many years, I denied that. It wasn’t politically smart to do so, but I admit it now. It was a different era,ŌĆØ Meek said. ŌĆ£I spent the rest of my career at Ole Miss dealing with these issues trying to reshape the image of the University of Mississippi.ŌĆØ

As a photographer and assistant vice chancellor for public relations at the university for most of his adult life, photographs and image defined Ed Meek. Sixty years and a Facebook post later, images continue to define him.